Your Research. Your Life. Your Story.

A magnetic community of researchers bound by their stories

Every researcher has a story. What’s yours?

What it's like to be a paleontologist mom

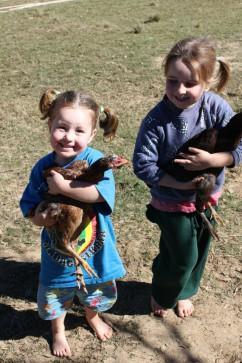

Family Photo

Exploration and paleontology have always been my passion. While most of my job involves sitting at a desk and typing away at my computer, I am fortunate that for three months a year I live in a tent, explore remote places, and dig fossil bones out of the earth. In a field where historically, paleontologists are often viewed as “old guys digging up dinosaur bones,” it has been gratifying to help expand people’s minds about what my research field is. But, being a field-based female scientist, and balancing work with family has always been a juggle that has required a lot of creative solutions.

Madagascar has always been the focus of my work, and like many others before me, I was drawn to the island due to its many bizarre plants and animals. The island has been fully isolated for nearly 90 million years, giving its creatures plenty of time to explode into all sorts of amazing niches – yet how these groups arrived to Madagascar still remains largely unknown. Much of my work involves trekking out to remote areas to find rocks deposited during the Cenozoic time period (when many of the modern groups are thought to have arrived), looking for fossils, and trying to shed light on what was going on during this time.

I have been coming to Madagascar since 1998 and am very fortunate to have a husband that also does research and fieldwork on the island (studying living lemurs and conserving the rapidly dwindling habitats they live in). For many of the early years we returned to Madagascar, always without children. Our friends were thrilled to hear we were married in 2002, and soon after, the questions began – “When will you have kids?” “How many kids will you have?” “Do you want girls or boys?” They were puzzled that first of all, I was two years older than my husband, and second that I was thirty and childless – one well-known Malagasy blessing states “fitolahy sy fitovavy” which roughly translates to “may you have the good fortune to have seven boys and seven girls.”

Camping on the beach for paleontology

In 2006 when I arrived pregnant, I think everyone gave a huge sigh of relief. “Finally,” I could hear them thinking to themselves “that wife of Mitch’s has finally figured it out” (… if we had waited much longer, I think we were going to get a little lecture on the birds and the bees). Our kids were born in 2006 and 2008 and have Malagasy middle names – Rianala and Sahondra; they have come to Madagascar every year since they were born. The early years of fieldwork with them was hard – while reflecting back I tend to romanticize it, I can still remember how both my husband and I were both overwhelmed with guilt and worry leading up to our first trip. We are actually quite fortunate that Madagascar is a forgiving place to do fieldwork – the island has no deadly, poisonous snakes or spiders, no large dangerous animals (such as elephants, jaguars, hippos, and lions), and due to its isolation, many of the diseases present in other countries are less prevalent. But we do have our share of worries – scorpions, malaria, plague, typhoid. The long list of items to plan and prepare for is now well-worn in my mind, but it took many years of tweaking.

Sahondra in the rainforest of Ankadivory

View from the toilet (at Ankadivory)

Hanging out at camp (Ankadivory)

Our summers often amount to an intricate “dance” of one parent leading their respective research team, and the other both working and supporting. It has also helped bring us closer together personally and in collaborating professionally – my husband has a great eye for collecting fossils, and I help study the growth and health of his beautiful diademed sifaka lemurs. Working in the same regions for nearly two decades, we have a strong network of local friends and babysitters that have helped us immeasurably to manage both the research and kids.

Sahondra carrying her friend

Fun getting muddy

Chasing chickens

Being carried on the long hike to Vatateza

Appreciating local wildlife

I am often asked about the things I couldn’t live without (especially when the girls were babies). A few key things come immediately to mind:

1) A good set of quick-dry cloth diapers – not only would it be depressing to create so much waste in the field, the cost of one pack of diapers can be as much as someone’s daily wage. Cloth diapers (quick-dry fleece), with inserts (and inner liners) were the only way we could function without running water and electricity (and in a pinch, you can even dry them over a fire!).

2) Baby carrier – when the kids were little (and even when they were quite large), baby-wearing was the only way we could function. The kids were happy to be portered around on my back, could be passed off to willing Malagasy babysitters, and even hiked many hours and kilometers to our remote camps in the rainforest.

3) The book “Your Child Abroad” – while most books are hopelessly irrelevant for bringing kids to the field, this one is a breath of fresh air. Specifically targeted for people bringing their kids into remote regions, it provides valuable medical advice (for example, which symptoms should cause one not to worry, and when one should immediately evacuate), and also practical support, and wisdom.

4) Ketchup. Our kids are great eaters (and much more patient with many months of rice for breakfast than any of the students I have ever brought to Madagascar), but there are limits. When the occasional odd or strange food graces our plates, ketchup is the magic that can always work wonders.

Rianala helping jacket fossils

Sahondra cleaning a fossil jacket

On the long rainy hike to Vatateza

On the long rainy hike to Vatateza (carried by dad)

I am continually struck by the ways having my kids in the field has opened my eyes. For example, kids just play – they don’t care if you speak their language, they don’t care what color your skin is; the desire to play, laugh, and explore is really universal. Falling into a rice paddy or farting loudly is funny no matter what language you speak – no translation necessary. Having the kids here has also made me realize how isolated many mothers are in North America. Seeing support networks of family and friends, especially for raising young babies, showed me how much we could all gain from having more of a “village” mentality. Lastly, kids are resilient – much more resilient than we give them credit for. Madagascar is unpredictable, and my kids have learned the hard way that a 7-hour trip to the field can sometimes take 24 hours. It seems like a valuable lesson to learn that life is not always easy – being in the field helps one to appreciate the small things (like a sunny day after two weeks of rain, dry socks, a warm sleeping bag, and discovering a lost chocolate bar long stashed away).

Bringing my children to Madagascar has also started conversations about the needs of women and children in our area – ones I am not sure would have happened otherwise. It prompted the creation of a women’s association in our area, and workshops on health and family planning. Our Malagasy friends have seen our kids come as babies, grow up, and now play with and babysit their kids. We have seen their kids grow up, become research guides, get married, and have kids and grandkids of their own. With nearly 20 years of visiting Madagascar, this thread of connection has led to meaningful relationships that I am truly thankful for.

Moms carrying kids

Rianala with her friends

The long hike to Vatateza

Rianala with her new friend

Friends often say to me “my kids would never do that – they are too obsessed with their phones or reliant on technology” (television, computers, etc.). To that, I say – give it a try, they might surprise you. Take them on a weekend trip camping or have everyone “unplug” for a few days. For all that technology has done to bring us closer together and make the world smaller, it has also forced us to be too distracted around those that we are right next to. In Madagascar, with no electricity and internet, when dark comes we retreat to our warm tents to read, talk, tell stories, and listen to the raindrops and night creatures as they awaken.

I would never claim to be the perfect example of a parent balancing “work and life” – I have had my share of moments I am not proud of – being impatient with my kids and struggling with the lack of freedom, and exhaustion. Leading a research team is hard enough – it sometimes takes every last bit of energy I have to try and juggle doing both (and it is often not graceful). Sharing the responsibility with my husband is the only way that it works for us, and I am grateful every day for the chaotic circus we desperately try to co-manage together. When I see my kids laughing and playing with their Malagasy friends by the rice paddies, climbing a tree to pick ripe guavas, or the glint in their eyes when they find a chameleon in a nearby tree, it feels worth it.

Chameleon discovery

Will my kids grow up to be field biologists or paleontologists? Who knows what the future holds – the iterations we have been through started with “princess” and “fairy,” through “doctor,” “donkey-farmer,” and now my youngest at age nine has decided that she wants to be an electrical engineer. My oldest (eleven) just told me she wants to be a marine biologist. What do I hope for them? Maybe that they will have a broader view of the world, and acceptance of other people. That they will learn to be more resilient when faced with challenges. That they will appreciate the beauty of nature around them, and care about the stark reality - that in Madagascar it may all be gone before they are old enough to have kids of their own. But, perhaps my biggest hope is that they follow their own paths and learn that the world is a vast and beautiful place to explore.

Sahondra playing with friends

This is a story by Karen Samonds, Associate Professor at Northern Illinois University and Co-founder of the NGO Sadabe. This story was published on January 17, 2019, on the blog Field Secrets (available here), and has been republished here with permission.

Comments

You're looking to give wings to your academic career and publication journey. We like that!

Why don't we give you complete access! Create a free account and get unlimited access to all resources & a vibrant researcher community.

Your Research. Your Life. Your Story.

A magnetic community of researchers bound by their stories