Science communication: Everything you need to know about it to thrive

Science is important for many reasons, among which is the ability to amaze us with what we see and experience. Almost everyone has experienced moments when science has unravelled or created a puzzle of the world and the universe.

As far as science is concerned, science communication (Scicom) is the most significant concept to grasp because it adds value to scientific discovery by "transmitting" it to a bigger audience. Communicating science is a necessary step towards developing a career with high impact.

The field is devoted to bridging the public-scientific gaps, encompassing topics from the natural sciences, applied sciences, engineering, medical science to environmental sciences. Science communicators translate challenging science concepts into everyday language. It's simple to understand why mastering science communication is utterly important for any scientist or author in science-related areas.

We will learn the ABCs of science communication in this blog post. We will cover everything you need to understand how science communication works and what you need to do regardless of your scientific field of expertise. You may also want to check out our other article in this category.

What is science communication?

Communication of science encompasses a range of practices that convey scientific information, methodologies, and results of scientific research to a general audience in a meaningful, comprehensible, and useful manner.

Science communication should be appropriate for a wide range of audiences, no matter their professional background. STEM professionals (science, mathematics, or engineering) shall be able to read a scicom article in the same way of a lay person or a professional from fields unrelated to science.

Public communication of science can take many forms and be tailored to various audience types. Multidisciplinary by nature, this field draws upon a wide array of academic fields and methods of expressing ideas. Science communication is the dissemination of research-based information among a range of stakeholders – individuals, organisations, and governments.

Some organisations even have dedicated science communication professionals working on a daily basis to publish articles that inform the general public, trying to emphasise the relevance of the science performed in that institution. There are also dedicated portals to science communication and press releases, like the Eurekalert.

Have you ever tried to publish a science communication piece through your university or research institute? Here is what you need to do it right:

A science communication program must perform four interconnected steps:

- The first step is to identify which scientific discoveries are important for decision-making.

- The second step is to identify what people presently understand.

- The third step is to provide communication that helps eliminate the essential information gap of what individuals understand and what they need to be aware of.

- The fourth step is to assess the effectiveness of those communications.

Using these four steps, you can easily assess how successfully and seamlessly science communication occurs for a variety of audiences.

Communication that is scientifically sound requires expertise from several sources, including (a) subject-matter experts, who can identify the accurate information; (b) analytical scientists, who search for the right data in order not to miss or obscure them; (c) social, behavioural and economic scientists for developing and evaluating communication strategies, and (d) communication specialists, who create channels of communication that are trustworthy.

And the ultimate tip is be concise and avoid jargon by all means. That's the essence of impacting real people out of academia.

Who is a Science communicator?

In science communication, each organisation has its own duties and responsibilities, and the people who are responsible for doing so are called science communicators.

Using science communication to bridge the gap between the interests of the various groups and stakeholders involved in public policy, business, and non-profit organisations can be effective. In the context of scientific misinformation, this may be especially important, given that it spreads rapidly as it lacks the constraints of scientific reasoning.

The examples below show some classes of science communicators:

- Science journalists are a common sight in national magazines and newspapers. These are specialised folks, who can dive deep into science-related topics, while keeping communication seamless.

- The University Press Office is responsible for making sure students and the public are aware of the groundbreaking research being undertaken by their faculty members. The Press Office may also be called the Media Office.

- There are dedicated staff members employed by communications departments of science-related organisations to design and update websites and social media accounts. They are particularly called the digital content managers.

- University, non-profit organisations, professional associations, and even museums have Public Engagement Coordinators to facilitate public events on scientific topics. Science and the public are brought together in engaging, meaningful ways by public engagement coordinators in order to increase public understanding of science.

- Companies that provide healthcare consulting services employ medical writers to evaluate clinical data and prepare clinical communication materials aimed at healthcare providers and other key decision-makers. Writers in the medical field are involved in public policy, public relations, special events, and biomedical communications.

- More recently, we have seen the rise of Science Influencers, particularly Youtubers, but also Instagramers and people navigating social media like masters. Some media are specific to the scientific community like ResearchGate, some are broader, like Twitter. Generally, lives, videos and visual memes are the best weapons of science communicators that work through social media.

Why is science communication important?

Imagine that groundbreaking discoveries are happening in the scientific community regarding vaccines, healthy ageing or nutrition, isn't it essential for the community to be made aware of them? It's rhetorical, we know that you agree.

Particularly when scientific misinformation, i.e. fake news, becomes a real problem, good science communication becomes a crucial factor of counterpoint. As an added benefit to society, Scicom makes science accessible to a wide variety of individuals. It is a powerful tool to make the community aware of scientific discovery.

Consequently, communicating science to "the outside world" is an entirely separate field. In addition to assisting society at large, communicating with the public can also benefit a researcher, by spreading the word about their latest findings, fostering new cross-disciplinary collaborations, building their visibility, and presenting them with new opportunities.

Communication about science also informs the public about how funding is used and what happens to tax dollars in a scientific world. This is often crucial for spreading the word and ensuring public support for scientific research funding. It also plays a role in integrating science with other beliefs and values of the various communities. A more scientifically educated population might also benefit society and governments, since a more democratic society is based on informed voters.

In addition to benefiting society, science can also benefit individual citizens. Science can simply be entertaining, such as popular science or science fiction shows or novels. A background in science can help us navigate an increasingly technological society. The application of science can influence ethics-based decision-making (for example, the relationship between humans and the climate or the moral principles of science).

Investing in the sciences is crucial to the future of our economies, environments, and societies. One of the best ways to inspire this is through effective public science communication.

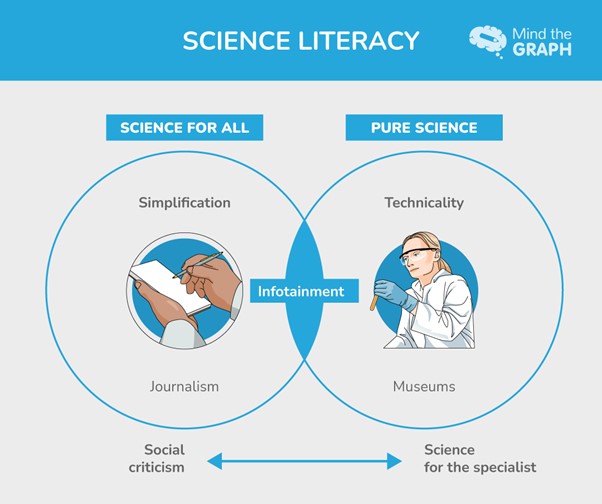

How to communicate science without oversimplifying it

Inspired by the American Association for the Advancement of Science and it's article on "how to communicate science without dumbing it down", here are a few elements to guide you in this field.

Oversimplification to communicate science is indeed something that bothers scientists all over the world. The beauty of science is often on it's complexity, but when one really gets it totally, there is no downside in communicating it in a straightforward and simple language.

Here are the suggestions from AAAS, which we endorse:

- Make it into a story everyone can relate to: practise the storytelling and make them dream together with you. Knowing the impact of the scientific discovery in real life may help the audience realise the importance of what you're explaining. Transform the "facts" into "stories".

- Don’t get bogged down in all the details: your lau audience does not need to know all the details. They can't even grasp it, so why bother with technicalities? Not everyone wants the same level of detail, be straightforward and focus on the message.

- Find a good analogy: when you relate to something that people already know, you can more easily teach them a new concept. Use it in abundance and try to compare scientific findings with normal situations or objects. Example: using the image of a "scissor" when talking about the "molecular alteration of an enzyme that cleaves a protein" turns a microscopic event into something tangible.

- Make use of images whenever you can. Sometimes it is hard to imagine what science means, but if you follow the principle of "show, don't tell" people will get it easier.

- Think about the tone of voice and language that you are using: talking to a non-scientist is not like talking to a toddler. Act normal, just focus on avoiding jargon and use vocabulary that you would use in a regular conversation with an adult.

- Share all the information needed to follow along: assume that your audience does NOT have some background knowledge on the topic and provide plenty of opportunities to dig deep into it.

- Ask open ended questions: this is thought-provoking and foster audience's curiosity. Start the conversation by making people think about the topic and let them contribute with their ideas.

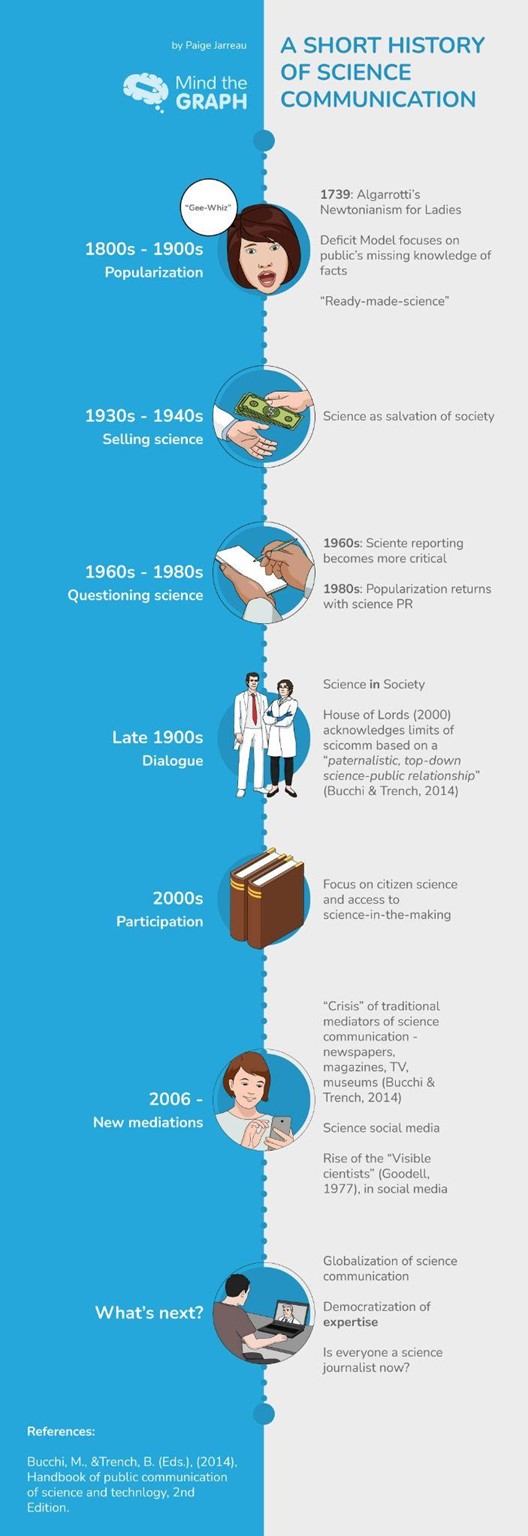

How did it all start? A look back at science communication tradition

Around the turn of the 19th century, the British Science Association was formed in an effort to address the fact that science had been neglected in the UK. The first meeting of the society took place at York on 26 September 1831, where one of the society's objectives was to get more attention from the general public to scientific matters.

After that, various nations made efforts to draw attention to scientific matters. The steam-powered printing press made it feasible to print more pages per hour, resulting in more affordable texts. With the gradual drop in book prices, the common classes could afford them. Mass audiences could now access informative and affordable texts.

Scientists were able to communicate their knowledge in a way that was accessible to the general public during the 20th century thanks to new science communication groups at the time. In the UK, the Bodmer Report published in 1985 by The Royal Society revolutionised public communication of scientific research.

The report aimed to identify the extent to which public understanding of science in the United Kingdom was adequate for an effective system of government. Professor Sir Walter Bodmer, distinguished scientists as well as Sir David Attenborough presided over the committee.

A principle of the report implied that every youngster should be acquainted with science and that teachers who are well qualified in the subject area should be tasked with introducing it to them from a young age.

The urge for relevant technological advances during the World War II changed everything: science finally matters for the lay public and governments alike

Public opinion of scientists shifted from great praise to resentment following the second world war, both in Britain and the United States. Due to the withdrawal of the scientific community from society, the Bodmer Report identified flaws in the funding of scientific research.

By expressing to British scientists that they were responsible for publicising their research, Bodmer used to promote science communication to a wider public audience. COPUS (Coalition for Public Understanding of Science) was established in response to the publication of the report and in collaboration with the Royal Society, the Royal Institution and the British Association for the Advancement of Science. As a result of this engagement, the public awareness of science and technology began to be taken more seriously.

Research organisations were strongly encouraged and then forced by the European Commission to communicate their research work and results effectively and widely to the general public. In order to achieve this, they have adopted a communication approach that made the project more visible to the public via a more comprehensible language and appropriate promotional channels and resources.

A number of facets of academic research and curriculum development have made science communication a focus. While it has become more prominent recently, its history is vast and interesting.

Since the mid-1930s, the term "science communication" has gained popularity for as long as science has existed. Communicators of science should understand science, appreciate its subtleties and be familiar with its extensive, sophisticated, and complex knowledge base.

Historically and currently, this topic is covered extensively in the field of Science and Engineering, an area that emphasises science communication.

In addition to increasing public awareness of public science through mass media, the popularisation of science also improved communication among scientists.

Throughout history, scientists communicated their insights and discoveries through print, but the number of publications on different subjects dropped.

A successful career in the sciences was reliant on publications in specialised journals in the 19th century. The increase in popularity of science in the late 19th century resulted in publications like National Geographic and Nature attracting large audiences and generating substantial revenue.

Science communication today

There are many ways to communicate science to the public nowadays. Media interactions are broadly divided into three types: conventional journalism, live events and online engagement. Let’s elaborate on those.

Conventional journalism

Conventional or traditional journalism, such as newspapers, media outlets, broadcasts, and radio, tends to reach a large audience. Science information was traditionally accessed in this way by most people in the past.

A traditional media outlet will usually publish well-written and well-presented content, since professional journalists put it together. Journalists frequently communicate in one-sided, one-way fashion, which makes interaction with the public impossible, and science articles are often focused on a narrow audience, making it difficult for them to see the whole picture from a scientific standpoint.

As another drawback of traditional journalism, when mainstream media picks up a story about science, scientists have little control over how their research is portrayed, potentially leading to misunderstandings or incorrect information. As a result, this gradually improved over time, and nowadays, we have articles written by scientists or professionals.

Live Science events

In the second category, live science events are organised, including presentations at museums and campuses, discussions, science performances, science exhibitions, and science fairs. Whether done in person, online, or by a hybrid of the two, public participation or budding researchers can engage the public in science communication through such events.

In addition to being more personalised, this approach allows scientists to communicate proactively with the public, enabling two-way communication. Scientists can also control the content more easily when using this approach. Among the disadvantages of this method are its narrow audience reach, the fact that it uses a lot of funding, and the likelihood that only individuals with a scientific bent will be inclined to participate.

Online engagement

The third category of science communication is through online engagement; for instance, webpages, weblogs, discussion forums, podcasts, and other social media can be used. A well-designed online method of communicating science can reach a wide audience, can provide a direct line of communication between researchers and the public. Researchers can control and have immediate access to the content.

Furthermore, it has been found that scientific communication online improves the visibility of scientists by increasing references, increasing publication rates, and fostering collaborations with different individuals.

In addition to one-way communication, online communications are also available in two-way fashion, at the discretion of both authors and audiences. While the internet is very useful, it has one important drawback: it can be difficult for one to control how someone can use the content. Regular maintenance is also required and updates have to be made.

A visual approach to communicating science: that's 21st century approach

Throughout the 21st century, visual culture has become more and more significant in shaping the science community. Thus, visual art has become a powerful means of communicating science.

There has been an upsurge of a global movement of scientists, educators, and communication professionals committed to better science communication over the past two decades.

A recent pandemic caused by COVID-19 showed the impact of these movements. We have seen plenty of misconceptions during this period, but on the other hand, we have also seen countless notable scientists convey info about the pandemic to the general public in an easy-to-understand, plain-language format.

Articles and information were presented in the form of visual graphics that made it very easy for people to spread this information across almost any type of audience.

A culture engulfed in visual elements has made communication in scientific and non-scientific communities a much more visual endeavour. In recent years, graphics and illustrations have been one of the most important means of communicating scientific information.

Visual elements, as well as all content, have a societal, educational, socioeconomic, and monetary purpose. In order to fully understand the potential meaning of a text and visuals, we must consider its context and audience. Science communicators must be aware of their audience when designing visual communications: they must know who they are communicating to. Check out ‘How to create a poster.

Various audiences can benefit greatly from the visual communication of science. In this way, it works well for both parties and makes the information spread in an accessible and comprehensible manner.

Charts, graphs, images, and other visuals can help you avoid jargon and make the audience more comfortable with the topic. “A picture speaks 1,000 words" and science is clearly a place where this is true - even when communicating to other scientists.

Visuals are engaging for presentations in front of a large audience. Take for example the slides in TED Talks: they use pictures and graphs but very few words.

Providing scientists with an empowering graphic design tool for science communication

Science can be communicated in various ways, but the best way is through images and posters that can easily transmit science to every target audience.

Mind The Graph has made it effortless to spread scientific knowledge around the world. Science of every complexity can be displayed in the most engaging way with a tool that helps you visualise it effectively.

It is possible to create research illustrations, research outputs, posters, and so on and so forth. Scientists already use Mind The Graph to their advantage, and they are maximising its benefits.

Using this, science communicators can explain science in a way that is easily understood by others in their own words. The best part is you can try it for free to find out for yourself how easy it is.

Science Communication is effective if it reaches recipients with their intended information in a form that they will be able to use. In order to reach that objective, scientists with expertise in a particular field must work closely with professionals with communication expertise in conjunction with those skilled in managing these processes.

We hope that this has covered everything you could possibly want to know about science communication. The aim is to spread vast knowledge of science around the world so that everyone can benefit from it.

Take a look at Mind the Graph and use it for free!

References

- The sciences of science communication, Baruch Fischhoff, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Aug 2013, 110 (Supplement 3) 14033-14039; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1213273110

- Bultitude, K. (2011), "The Why and How of Science Communication". In: Rosulek, P., ed. “Science Communication”. Pilsen: European Commission.

- Short, Daniel (2013). "The public understanding of science: 30 years of the Bodmer Report". The School Science Review. 95: 39–43.

- Dudo, Anthony (1 September 2015). "Scientists, the Media, and the Public Communication of Science". Sociology Compass. 9 (9): 761–775. doi:10.1111/soc4.12298. ISSN 1751-9020.

- Bodmer, Walter (20 September 2010). "Public Understanding of Science: The BA, the Royal Society and COPUS". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 64 (Suppl 1): S151–S161. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2010.0035. ISSN 0035-9149.

- https://www.aaas.org/programs/center-public-engagement-science-and-technology/reflections/how-communicate-science

Comments

You're looking to give wings to your academic career and publication journey. We like that!

Why don't we give you complete access! Create a free account and get unlimited access to all resources & a vibrant researcher community.

Subscribe to Manuscript Writing

Translate your research into a publication-worthy manuscript by understanding the nuances of academic writing. Subscribe and get curated reads that will help you write an excellent manuscript.