Your Research. Your Life. Your Story.

A magnetic community of researchers bound by their stories

Every researcher has a story. What’s yours?

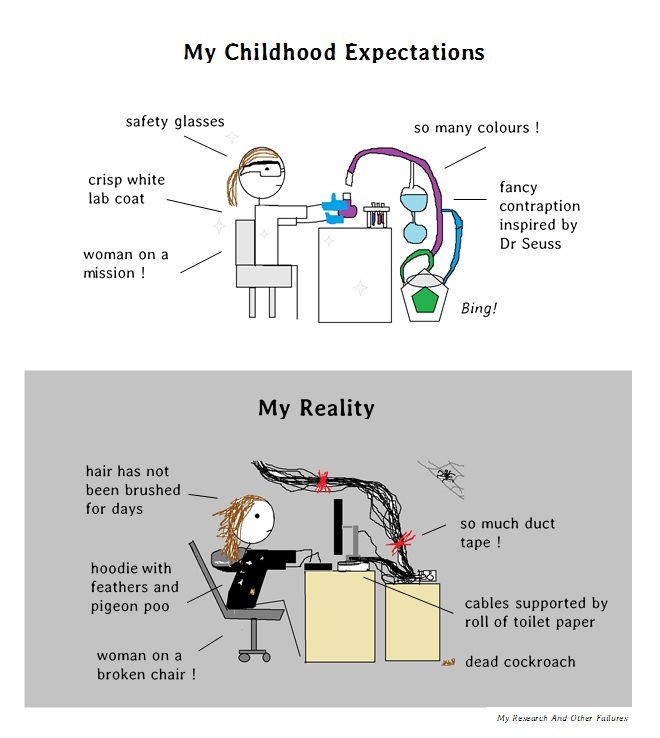

Lab truths: Everything I knew about laboratories was wrong

When I was younger, I thought research happened in white rooms. White walls, white floors, white benches, white coats. I imagined that everything in these rooms would be spotless and practically sparkling, like a scene from a skin care commercial. In my final year of high school, I said I didn’t want to be a researcher, mainly because I couldn’t picture myself working in such a sterile and sober place.

How wrong I was.

The pigeon shed has a concrete floor and a corrugated iron roof. It’s a 15-minute walk from clean drinking water and a toilet. There are always cobwebs and dirt, no matter how much time we spend cleaning. Every trace of food needs to be kept in a steel box, to avoid attracting rats.

And this was before we even added the pigeons. Pigeons are incredible creatures. As far as I can tell, their greatest joy in life is to splash water onto their food, then stamp on their food, and then poo on it. Meanwhile, they shed huge amounts of dander, a white powder like dandruff, which somehow travels upwards and outwards so that it covers everything in the room – like snowflakes, but made of skin.

For four months, this place was my research facility. And I loved it. Sure, I couldn’t collect data when it rained (too noisy), but it was convenient (except when I needed to go to the toilet), and the pigeons didn’t seem to mind living there (except for maybe Anxious Pigeon, but she doesn’t really like anything). I would have happily continued to work there, if I could.

Unfortunately, I could not. Two days after Christmas, I received a call to say that the air-conditioning had broken, and we that should probably panic.

It was the peak of summer in Melbourne. The temperature outside was often over 35°C. I half-heartedly tried to convince the animal facility team that pigeons are actually desert birds, incredibly well-suited to heat (see reference). Not surprisingly, I was unsuccessful. A van was hired, a date was set, and we began the painful process of moving 10 aviaries, 10 pigeons, 18 lamps, 16 cameras, countless cables, and everything else that had slowly been gathering dander over the past five months.

My new research facility was, thankfully, only a few minutes away by van. I will refer to it here as “The Asbestos Building,” for no particular reason. I was told that it had functioning air-conditioning, a little room that I could use as an office, and a toilet. All excellent features.

The first things I saw when I entered The Asbestos Building were 1) a dead cockroach; 2) a cluster of buckets, half-filled, collecting the water that was leaking from the roof; and 3) another dead cockroach. A passing animal technician must have noticed my expression. She apologised for the mess and explained that they hadn’t had time to clean properly since the flood. I assured her it was fine, adding – with a laugh – that the dead cockroaches weren’t the best first impression.

“Oh no,” she said, with no hint of sarcasm, “those are normal.”

At this point, maybe I should emphasise that cockroaches and rats don’t usually have access to labs. Still, in my experience, labs are rarely, if ever, the sparkling white, silent, serious places that I once imagined.

There are unpleasant, permanent stains on my bench. Unidentifiable broken objects on the windowsill. Special waiting-for-the-centrifuge dance moves. Tie-dyed lab coats. Professors who hoard huge boxes of – as far as anyone can tell – dirty containers, dead worms and sand, which nobody is allowed to throw away.

Even as I write this, there is a yellow “CAUTION: WET FLOOR” sign outside my supervisor’s jellyfish lab. My supervisor just cheerfully informed me that, when he arrived this morning, there was more than 100 litres of water on the floor. The water from the leaking jellyfish tank made it halfway across the room next door, which happens to be my supervisor’s office, and now his carpet will forever smell of shrimp.

Maybe all of this is only true for zoologists. Maybe other labs are filled with shiny, flawless, expensive equipment. But in my experience, labs are more often filled with things that a postgrad made from masking tape and takeaway containers. We associate the word “laboratory” with beakers and test tubes filled with pretty, colourful liquids. I think a more appropriate symbol would be a handwritten note saying something like “OUT OF ORDER,” “DO NOT TOUCH ON PAIN OF DEATH” or “A PIGEON HAS ESCAPED. I AM TRYING TO CATCH IT. PLEASE DON’T OPEN THE DOOR.”

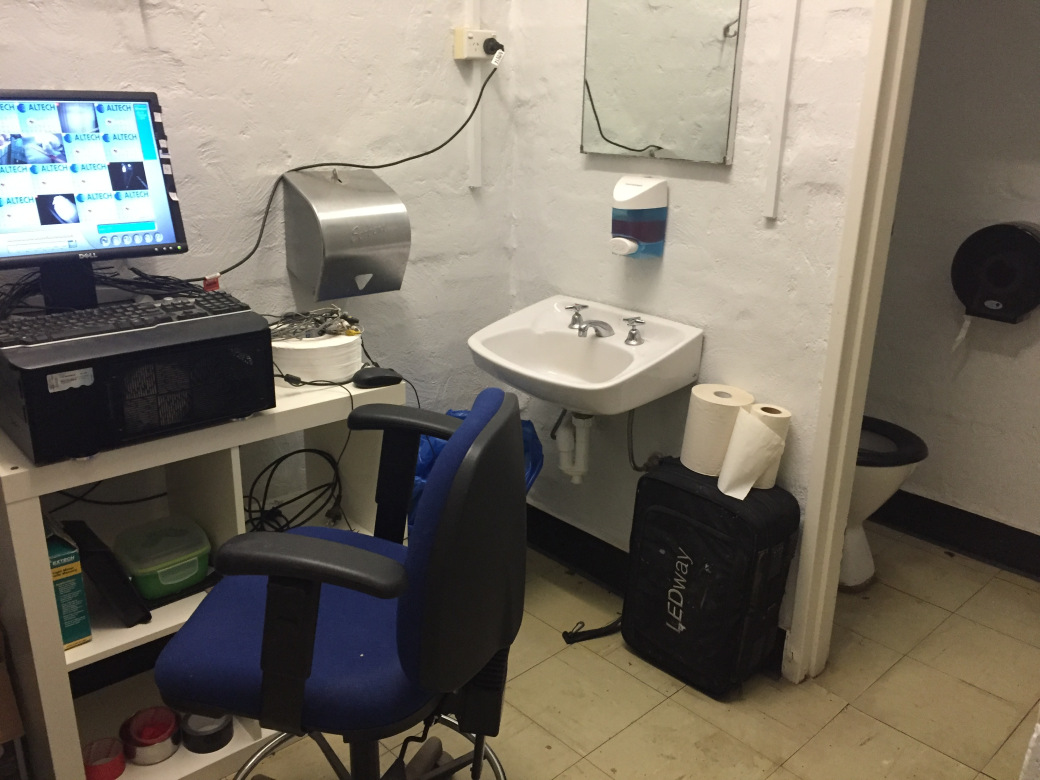

But in the end, all of this just becomes a way of life. Despite my misgivings, the pigeons and I settled into The Asbestos Building without too many problems. Sure, I need to dodge buckets of water each morning (they’re still trying to find the problem in the roof), and I’ve lost count of how many cockroaches I’ve caught (my record was 6 in 10 minutes). And I don’t get the office entirely to myself, since other people sometimes need to make use of it.

My lab office. Be envious.

I mean, I wouldn’t say it’s perfect. But at least there IS a toilet, right?

I sometimes wish I could show all of this to my high-school self.

“There – see?” I would say, “Think you’d be bored? I DREAM of boredom. Boredom would be amazing! It would mean that things are ACTUALLY WORKING.”

Maybe I should be kept out of high schools.

…

An additional note: A number of friends and strangers gave up their time to help me with The Great Pigeon Move to The Asbestos Building, and they are very much appreciated. Thank you.

Anne Aulsebrook (@AnneAulsebrook) is a PhD Candidate (Zoology). This story was published on February 14, 2017, on Anne’s blog, My Research and Other Failures (available here), and has been republished here with her permission.

Comments

You're looking to give wings to your academic career and publication journey. We like that!

Why don't we give you complete access! Create a free account and get unlimited access to all resources & a vibrant researcher community.

Your Research. Your Life. Your Story.

A magnetic community of researchers bound by their stories