Your Research. Your Life. Your Story.

A magnetic community of researchers bound by their stories

Every researcher has a story. What’s yours?

I was lucky to have a supervisor who recognized the progress I was making

At the beginning of 2014, I realised I had chronic fatigue. Physically, I was almost unaffected, but cognitively, I could only go for about 40 minutes before I began to experience the sort of cognitive fatigue most people would experience at the end of an extremely long day (headaches, inability to focus, difficulty recalling things). If I pushed through this, my brain seemed to work so slowly that I felt unsafe crossing the road.

After 9 months of trying to work out what to do about it, I was eventually referred to a psychologist specialising in fatigue, who suggested, among other things, that I resume working on my thesis. For one hour a week. Split over two days. Split into two 15-minute blocks, not approximately 15 minutes, but 15 minutes timed. Eventually this would increase, very gradually. We hoped.

I found this somewhat difficult.

Ok, I found this very, very difficult. One of the most difficult parts was not chucking the whole thing in as an exercise in futility. If I thought about how much work I still needed to do and divided this by the one hour per week I could work on my thesis, it was pretty clear I wasn’t going to finish it during my lifetime. Of course we hoped that the amount of time I could work on my thesis would increase, but I found it very hard to ignore the ‘hoped’ in that sentence.

Looking back, I can see I was dealing with extreme versions of the two fears that most PhD students seem to face at some point:

- Am I making enough progress? Will I ever finish the damn thing? And isn’t everyone else doing more than me, and getting ahead quicker?

- Is my supervisor happy with what I’m doing? Will our next meeting be supportive and productive or will I have to constantly defend what I’m doing and whether I should even be doing a PhD?

To get myself past these anxieties and to a more positive state of mind, I had to shift from judging progress against what I thought everyone else was doing—to whether it brought me closer to goals that were appropriate for me. Along the way, I had to learn that progress frequently wasn’t what I expected it to be.

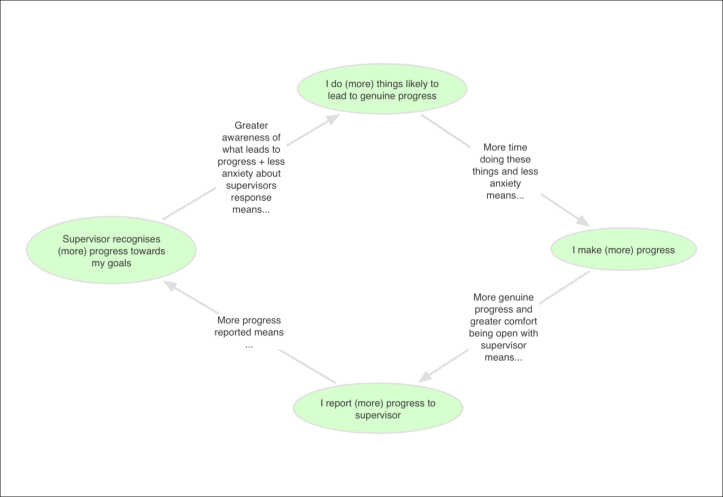

In doing this, I was very lucky to have a supervisor with a particular talent for recognising unusual forms of progress. This ability had already been useful in establishing an open relationship between us before I got sick, and I continued to benefit from it as I came to terms with my chronic fatigue. Every time my supervisor focused on the progress I had been making, I could feel some anxiety lifting. I didn’t have to devote resources to worrying about what he thought or trying to pretend that things were better than they were. Instead, I could focus on doing the things I needed to do to get better (which were often difficult, so his encouragement also helped me to keep going). By doing this, I began to make more progress, and was more confident that I would get a positive response if I told him what was really going on. Which in turn gave him more opportunities to see the progress I was making (this positive cycle can be seen in the diagram below).

In order to think about what progress meant in my circumstances, I first had to choose goals that were appropriate for me and make sure my supervisor was on the same page. Instead of just referring to milestones on the way to completing my thesis, my goals explicitly referenced my health and things I needed to learn how to do. Being clear on what I was trying to achieve was extremely helpful when it came to the critical reflection needed to recognise what progress actually looked like for me.

Goal 1: Increase time spent on PhD without damaging my health

The first thing my fatigue psychologist got me to do was establish a routine that I could complete each day without feeling excessively fatigued. This involved placing limits on the time spent in all aspects of my life from catching up with friends to watching TV. When it came to my thesis, it meant that I had to learn to stop working as soon as the timer went off, regardless of what I was doing at the time and whether I felt fatigued at the time. Getting my head around the idea that progress meant spending less time on my thesis took some time. This was one of the times when hearing my supervisor recognise this as progress was extremely helpful.

It didn’t take long for me to realise that an equally important challenge was learning to start as soon as the timer began. To do this, I would have something planned to work on and then try to stick to it, even if I began to think it wasn’t a particularly useful thing to be doing partway through. If I didn’t think it was an effective use of my time, I could reflect on it after I finished (this sort of reflection didn’t need to be included in my 30 minutes) and modify my plan for next time. Again, I had to change what I thought of as progress – I was working towards my goal if I spent 30 minutes – no more, no less – doing cognitively demanding work related to my thesis. Whether I felt that work was a good use of the 30 minutes at that stage didn’t matter.

Goal 2: Learning how to write the most difficult section of my thesis

Once I had developed the ability to work reliably on my thesis with a timer, I began to think about how to get the most out of the time I spent on my thesis. I decided to start working on the most difficult section of my thesis. My thoughts on this section were still rather tangled, it involved integrating a complex argument with a review of the literature (which I wasn’t sure I could pull off), and I found writing difficult in general. Overall, rather daunting! My theory was that if I was able to complete this section, I would know I could complete the rest of my thesis. The goal was therefore as much about learning the remaining skills I needed to finish my thesis as it was about completing one particular section.

By including learning skills as part of the goal, I could recognise that reading blogs on the Thesis Whisperer and books on writing, asking students and academics about their writing process, and experimenting with different approaches all counted as work towards this goal. Realising that my writing difficulties mainly stemmed from poor note-taking was a major sign of progress, even though it meant I would need to re-read and re-note-take for a significant number of articles (I did need to repeat this to myself a number of times before I, mostly, believed it. It was a relief to hear that my supervisor agreed.)

Can these goals have deadlines?

Another thing my supervisor had to come to terms with was that I sometimes wasn’t able to put any meaningful deadline on when these goals would be completed. While the deadline for any goal is an estimate that may need revising, this is a whole different level of deadline uncertainty.

As part of my recovery from chronic fatigue, we had to determine the rate at which I could increase the amount of time I work on my thesis. As it turned out, I can add an extra 10% each fortnight. However this rate varies from person to person and is determined by trial and error. Without knowing the rate that works for me, the best estimate of how long it would take to return to working 20 hours/week on my thesis was between 6 months and 6 years (or not at all).

Doing something for the first time, when you also need to learn how to do it, takes a lot longer than it would take someone who knows how to do it (e.g. your supervisor). Making it clear that you need to learn how to do something, or talking to someone with academic skills may result in a better estimate. However, the time taken to learn something new depends not just on the thing to be learnt but also on the difficulties faced by the student. This is especially relevant for students with a disability, illness, or neuro-diverse brains and so estimating the time it will take us to learn how to do something is particularly difficult.

This is not to suggest that illness, disability, or having a neuro-diverse brain should be used as a get out of jail free card to avoid ever estimating goals. In many cases I have been able to make some sort of an estimate (including a lot of contingency) and it was beneficial to do so. However, pulling a deadline out of thin air doesn’t provide any useful information and causes stress and anxiety to everyone when it passes by unmet.

I think this is something that supervisors and universities can be more proactive about, perhaps asking ‘Is it possible to estimate when XX will happen by?’ instead of starting by asking for a date. When asked for a date, my natural response has been to make something up and deal with the consequences later, and I’ve been surprised to observe some of my medical professionals make a similar response. Being clear that in certain circumstances it is ok not to know how long something will take is more likely to lead to an honest discussion, which will ultimately benefit everyone.

*The image above is an infographic of why recognizing progress is so critical, created by Ruth Mills, the author of this story.

This story was published on September 5, 2017, on the blog, The Supervision Whisperers (available here), and has been republished here with permission.

Comments

You're looking to give wings to your academic career and publication journey. We like that!

Why don't we give you complete access! Create a free account and get unlimited access to all resources & a vibrant researcher community.

Your Research. Your Life. Your Story.

A magnetic community of researchers bound by their stories