6 Critical ethical principles associated with research in traditional medicine

In recent years, there has been a substantial debate on the ethics of research in traditional medicine (TM). In general, the controversies have revolved around the unreasonable harvesting of medicinal plants from the wild, ethical accountability of researchers towards local knowledge holders, and the credibility of TM as a complementary and alternative mode of treatment [1]. Since increased publications are the only way to maximize research outreach, it is important to understand the ethical principles governing publication in TM journals. There are six broad things to consider here:

- Ethical policies and declarations

- Sustenance

- Scientific validation

- Informed consent

- Proprietary issues

- Reporting standards

1. Ethical policies and declarations

The Helsinki declaration outlined the basic ethics of human experimentation and marked the beginning of resolutions and policies in research studies. However, the Chiang Mai declaration (March 1988), the WHO Traditional Medicines Strategy 2002–2005, and the WHO general guidelines for Methodologies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine have a greater focus on the ethical principles for research in TM. For example:

- The Chiang Mai declaration endorses international cooperation and coordination for the conservation of medicinal plants to ensure their adequate availability for future generations [2].

- The WHO Traditional Medicines Strategy mainly focuses on policies related to the safety, efficacy, quality, access to, and rational use of medicinal plants [3].

- The WHO guidelines for Methodologies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine focus on the current major debates on safety and efficacy of TM and are intended to raise and answer some challenging questions concerning the evidence base. The document also presents national regulations for the evaluation of herbal medicines and recommends new approaches for carrying out clinical research [4]; for example, as per the document traditional medicines with a deep-rooted history of use can be directly taken to phase 3 clinical trials, after a toxicity study has been conducted.

- Additionally, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) offer a standard format for authors to prepare reports of trial findings, which facilitates complete and transparent reporting, and helps authors in critical appraisal and interpretation of data [5].

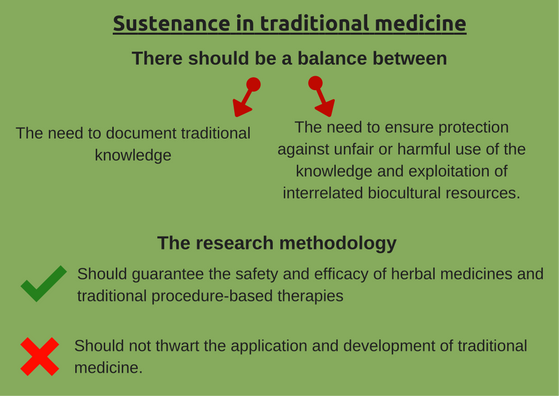

2. Sustenance is key

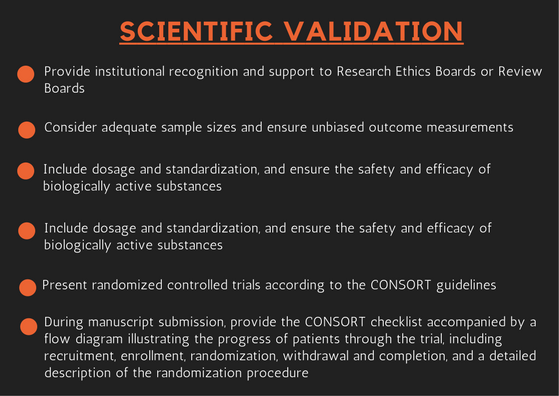

Scientific validation is the prerequisite for useful interpretation and wider acceptance of TM. Institutional recognition and support must be provided to Research Ethics Boards or Review Boards. Since the same TM may be used by different communities to cure different ailments, scientific validation in each case using standard or modified methods is imperative. Validation studies must consider adequate sample sizes and ensure unbiased outcome measurements. Validation studies should include dosage and standardization, and ensure the safety and efficacy of biologically active substances before large-scale clinical trials are conducted [3].

Randomized controlled trials should be presented according to the CONSORT guidelines. During manuscript submission, authors must provide the CONSORT checklist accompanied by a flow diagram illustrating the progress of patients through the trial, including recruitment, enrollment, randomization, withdrawal and completion, and a detailed description of the randomization procedure [6].

4. Informed consent

Informed consent is a term used to mean informed, voluntary, and decisionally-capacitated consent obtained from study participants. The simplest rationale for informed consent is that it protects participants’ health, welfare, and personal integrity. Alternatively, informed consent safeguards the informants against such deontological offenses as assault, deceit, coercion, and exploitation [7].

Researchers evaluating traditional medicines need to recognize that the customary owner, and often that owner’s country of origin, holds rights over the knowledge being evaluated. This has consequences for patenting. If a patent is sought by a nonindigenous group, prior informed consent and benefit-sharing with customary owners must be established. TM journals protect intellectual property rights by ensuring that the origin of traditional knowledge is traceable, prior informed consent of knowledge holders and source communities is documented, knowledge holders retain rights over knowledge, due credits are given to knowledge holders, and benefits are shared equitably among contributors [8].

6. Reporting standards

Unfortunately, there is no widely accepted template for documenting TM knowledge. However, such studies must be supported by extensive data, especially if the knowledge is documented to develop innovations. Information on gathering, cultivation, preparation, storage, and seasonal and altitudinal variation of active compounds is of prime importance in TM studies. Likewise, clinical information on TM must state symptoms, dosages, toxicity, efficacy and side-effects, as well as methods of administration. While there is no universal rule stating the level of individual or community contributions that must be included in documentation efforts, failing to acknowledge TM knowledge holders with a claim to the knowledge may lead to charges of misappropriation of intellectual property [9].

To develop a reliable and coherent body of knowledge in TM, or for that matter, in any field, it is essential to publish articles in peer reviewed journals. Publication ethics are an essential part of research dissemination as ethical principles lend support, adequacy, and credibility to the scientific method. It is, therefore, extremely important for researchers in the field of traditional medicine to understand, agree upon, and follow the standards of expected ethical behavior as outlined in this article for publishing in peer reviewed TM journals.

References

- Report of the International Bioethical Committee on Traditional Medicine Systems and Their Ethical Implications, 2013. SHS/EGC/IBC-19/12/3 Rev. Paris (http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002174/217457e.pdf)

- Bodeker G, Kronenberg F. A Public Health Agenda for Traditional, Complementary, and Alternative Medicine. American Journal of Public Health. 2002; 92:1582-1591. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3221447/)

- WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy, 2002-2005. WHO/EDM/TRM/2002.1 (http://www.wpro.who.int/health_technology/book_who_traditional_medicine_strategy_2002_2005.pdf)

- WHO General Guidelines for Methodologies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine, 2000. WHO/EDM/TRM/2000.1 (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/66783/1/WHO_EDM_TRM_2000.1.pdf)

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials BMC Medicine 2010, 8:18 (http://www.consort-statement.org/)

- https://www.elsevier.com/journals/journal-of-traditional-and-complementary-medicine/2225-4110?generatepdf=true

- Manson NC, Onora ON. Rethinking Informed Consent in Bioethics. Cambridge University Press. 2007. (https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/rethinking-informed-consent-in-bioethics/86303F0B7A7B1922DF91C7B1A8982957)

- Gupta, AK. Policy Gaps for Promoting Green Grassroots Innovations and Traditional Knowledge in Developing Countries: Learning from Indian Experience. 2013. (https://ideas.repec.org/p/ess/wpaper/id5281.html).

- Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Killen J, Grady C. What Makes Clinical Research in Developing Countries Ethical? The Benchmarks of Ethical Research. Journal of Infectious Disease. (2004) 189 (5): 930-937.doi: 10.1086/381709. (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/189/5/930.full.pdf+html)