Biology has diversified since the era of intrepid pioneers of botany and zoology cataloging and classifying specimens they collected on their travels. The molecular biology revolution of the 20th century introduced dozens of new life sciences disciplines, including biochemistry, microbiology, and immunology. Each of these fields fall under the umbrella of life sciences research. Despite their immense differences in scope, there are a few points that every biologist must pay attention to when preparing their manuscript. I would like to introduce my tips that will help any life sciences researcher—irrespective of whether the manuscript is still in the planning stage or the submission package is almost ready to be sent off.

Decide the audience

The most vital question when preparing any scientific manuscript is, – “Who is this intended for?”

It should be easy to answer, but sometimes we need to pause for thought. Who will read your life sciences manuscript? An experienced colleague in your field is an obvious answer, but not all your readers would belong to your field. Perhaps your breakthrough findings in pharmacology research will end up in a drug discovery journal, but it may even be a good fit for a major medical journal like NEJM1 or The Lancet2, where physicians and pharmacy professionals stay updated on the newest insights.

The assumed knowledge of the audience for each publication differs, which leads me neatly to my next point.

Tailor to the audience

When you spend day after day laboring over your research, you may take certain words and concepts for granted. However, a zoology paper will contain words or phrases that are uncommon in microbiology research and vice versa. Perhaps you do not need to explain what “DNA” means, but how about a sentence like this one:

We conducted GO and KEGG analyses to determine the DEGs between patients and healthy controls

Now, a molecular biologist studying transcriptomics will likely know GO3, KEGG4, and DEGs5. But how about a biologist from a field such as ecology who is part of a multidisciplinary team? We cannot take knowledge for granted, so we must ensure that technical jargon is avoided or explained if avoiding it is unfeasible.

While tailoring is important, we must be careful not to oversimplify things until we say something unscientific. It might be tempting to describe a novel insight into a gene associated with human intelligence as being “the intelligence gene,” but grandiose or inaccurate descriptions can harm your message. Furthermore, making the text flowery is not encouraged in life sciences fields as this can deviate your reader’s attention from your study’s focus.

Materials and methods need details

It is easy to skip over details when working to meet deadlines and word limits. Nobody expects you to transfer every single detail from your lab book to your life sciences paper, but it is vital to write so that another researcher can reproduce your findings in their laboratory.

For example, if I saw a sentence like this in an immunology paper, I would flag it with the author:

Membranes were incubated at room temperature with a mouse monoclonal antibody to CD4 (Abcam).

The sentence is missing crucial information such as the incubation temperature and time, the identity of the antibody (Abcam offers 27 antibodies of this description), and the antibody dilution and diluent used. Your research paper should not be an instruction manual, but your methods must be replicable.

Take another example, where a PCR step—a common molecular biology technique—is described as,

PCR was performed using appropriate primers and repeated thrice

As replicates and repeats do not have the same meaning, this step is puzzling. Furthermore, without knowing the primer names, sequences, and design or manufacturing details, this sentence is an incomplete jigsaw puzzle.

Use discipline-appropriate terminology

Words themselves can mean different things in life sciences research. Take a term as simple as “expansion” in reference to cells. In botany8, this refers to the expanding volume of cells. However, those in stem cell research will have an entirely different understanding9 of this term, as “expansion” refers to strategies to proliferate stem cells.

If you’re submitting to a botany journal, this may not be an issue, but a journal like Nature10 attracts scientists of all fields. Here, a web search for key terms will usually reveal whether there are any competing definitions.

Make sure everything is ethical

Whether zoology, pharmacology, or molecular biology, ethical research conduct is critical. Peer reviewers and journals editors are responsible for what appears in their journal. They will be on the lookout for ethical violations, so you must affirm that all relevant guidelines were followed at initial submission. This is why declarations of competing interests, funding details, and ethical declarations cannot be overlooked. Journals will supply their own guidelines for preparation, but it is worthwhile to familiarize yourself with some of the most crucial handbooks such as the Declaration of Helsinki12, PRISMA guidelines13, and of course, your own institutional guidelines before any submission to make sure that your paper raises no concerns and that ethical life sciences research protocols are followed for humans and animals alike.

Image legends must stand on their own.

Without context, which legend sounds better to you?

- Fig. 1 IHC staining of Oct-4 in cancerous tissue.

- Fig. 1 Immunohistochemical staining of Oct-4, an undifferentiated cell marker, in a formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded lung adenocarcinoma section. DAB was used as a counterstain. Scale bar: 20 µm

I would choose the second. Figures must be understandable without the context of the whole manuscript. Even when the information can be found in the main body, we must ensure that we provide enough information in the image legend too. Your figure may end up in somebody’s biochemistry lecture slides or even another publication! However, make sure to not describe protocols extensively; this is a strict no-no for most high-impact journals.

Images – engaging but accurate

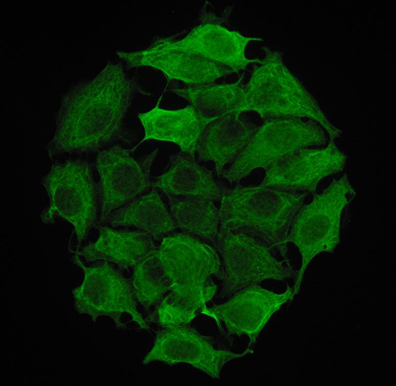

The adage “a picture speaks a thousand words” is true even in science. You can read about the cytoskeleton, but nothing helps you imagine it as much as a beautiful immunocytochemical staining.

Ideally, images are informative and attractive in life sciences papers. However, we must always be careful when preparing an image. It’s tempting to cut your western blots to save space, or increase contrast to show strong differentiation, but these changes are not always accepted by target publications. An innocent adjustment to make a more attractive image could even be considered a fraudulent manipulation. Whenever you adjust an image make sure that it does not mislead. Ensure that unedited files are made available at submission. Honesty is the key to success—even in the publication field.

If in doubt, artwork formatting can save you trouble. Putting together a good manuscript as a life sciences researcher can be daunting, Editage’s English editing service and wealth of online resources can make this process all the easier. I hope these tips provide solutions to some of the major pitfalls to make your submission a successful one.

References

- The New England Journal of Medicine. About NEJM. https://www.nejm.org/about-nejm/about-nejm (2022).

- The Lancet. About the Lancet. https://www.thelancet.com/lancet/about (2022).

- Ashburner, M. et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/75556

- Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27

- Zhao, B., Erwin, A. & Xue B. How many differentially expressed genes: A perspective from the comparison of genotypic and phenotypic distances. Genomics 110, 67–73 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2017.08.007.

- Abcam. https://www.abcam.com/products?sortOptions=Relevance&keywords=CD4&selected.classification=Primary%20antibodies–Monoclonals–Mouse%20monoclonals&selected.targetName=CD4 (2022)

- Vaux, D.L., Fidler, F. & Cumming, G. Replicates and repeats–what is the difference and is it significant? A brief discussion of statistics and experimental design. EMBO Rep. 13, 291–296 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/embor.2012.36

- Breuninger, H. & Lenhard, M. Control of tissue and organ growth in plants. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 91, 185–220 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0070-2153(10)91007-7

- Becnel, M. & Shpall, E. J. Current and future status of stem cell expansion. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 25, 446–451 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1097/MOH.0000000000000463

- Nature. Journal information. https://www.nature.com/nature/journal-information. (2022)

- Editage Insights. Q: Disclosure of conflicts of interest: what do journals expect from authors? https://www.editage.com/insights/disclosure-of-conflicts-of-interest-what-do-journals-expect-from-authors. (2014).

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (2013)

- Page, M.J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Kosach, V. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Cytoskeleton#/media/File:Cytokeratin_8.jpg (2015).

- Editage. Artwork Formatting. https://www.editage.com/services/other/artwork-preparation (Accessed 2022).

- Editage. Manuscript Writing. https://www.editage.com/insights/stage/manuscript-writing?refer=insights-nav (2022).

Comment