Publication and reporting biases and how they impact publication of research

This anecdote aptly illustrates a problem that plagues scientific literature—publication bias or reporting bias.1

Publication bias refers to a phenomenon in scientific reporting whereby authors are more likely to submit and journal editors are more likely to publish studies with “positive” results (i.e. results showing a significant finding) than studies with “negative” (i.e. supporting the null hypothesis) or unsupportive results.2 As a result of such a bias, important—albeit negative—results (e.g., a study showing that a new treatment is ineffective) may never reach the larger scientific community.3

This bias toward publishing studies with positive results is just one of the many different types of publication-related biases. As these biases influence publication decisions, it is important that you understand

1. what causes these biases

2. the different types of biases, how they impact publication decisions, and how to address them

3. the need to counter publication and reporting biases

Causes of bias

Reporting and publication biases are caused by many different factors. We’ve listed some of the main causes of these biases below:

- Many studies remain unpublished because researchers do not submit their work for publication, thinking that journals will reject their papers because they do not have positive or significant results to report. This submission-related bias has been termed the file drawer problem.4

- Journals may be biased toward positive results because negative results are less likely to be cited and can thus lower a journal’s impact factor.

- Study sponsors or funding sources may be biased towards results that favor their interests; it has been found that sponsors may withhold the publication of unfavorable results and that industry-funded studies have led to positive results far more often than studies that are funded or conducted by independent agencies.5,6

Different biases and how you can address them

The table below lists different types of publication and reporting biases that have been found to exist in scientific literature.1,7-11 It also offers some suggestions for addressing the different types of biases. It is best to address these biases directly, possibly while discussing the importance of the study in your cover letter to the journal editor.

| What it means | How to address this bias | |

|---|---|---|

| Publication bias | Studies with positive results are more likely to be accepted for publication than studies with negative results. | Describe the specific problem that your study results will help address. Point out that your negative results could help counter publication bias12 (in fact, there are now journals that exclusively publish negative results13) and specify the outcome or views that your study can potentially change. |

| Time lag bias | Studies with positive findings are likely to be published faster than studies with negative findings. | State why you think your study should be published without delay (e.g., because the results could warrant suspension of further trials or could affect how things are being done in practice). |

| Multiple publication bias | Multiple publications are more likely to be generated from a single set of positive or supportive results than from a set of negative or unsupportive results | If you have published a paper discussing a set of positive results, do not publish another paper using the same set of results (unless you are offering a radically different perspective or analysis; always cross-reference the first publication). |

| Location bias | Studies that report positive results have a greater chance of being published in widely circulated, high-impact journals than do studies with negative results. | First, do not hesitate to submit your paper to a journal with a high-impact factor. Researchers have found that one of the main reasons for location bias is that authors send negative results to low-impact factor journals, and not necessarily because journals are more likely to reject these studies.14,15 Second, when submitting to a high-impact journal, explain how the paper fits the journal’s scope and target audience, why the negative results are important, how the results challenge existing knowledge, and why it is important that your research reaches a wide audience. |

| Citation bias | Researchers are more likely to cite positive study results than negative study results. | If you come across negative results related to your study, be sure to mention them in your paper. Do not cite studies that only support your own results, as this could lead peer reviewers to suspect bias. |

| Language bias | The language in which a study is published depends on whether the study has positive or negative results; studies with positive results are more likely to be published in English-language journals. | Describe how your study results are of relevance to a global audience and hence should be published in an international journal that reaches out to this audience. |

| Outcome reporting bias | Researchers working on a study in which multiple outcomes were measured are more likely to report positive outcomes than negative outcomes. | Report any outcome that is relevant to your study, whether it is positive or negative. |

| Confirmatory bias | Findings that conform to a person’s (e.g., peer reviewer’s or journal editor’s) beliefs and hypotheses are more likely to be recommended for publication or published. | Relate your study to a previous study published in the journal. Explain that your study results may go against previously/widely held beliefs. Emphasize how your study results can address an issue or change existing perspectives. |

| Funding bias | Study conclusions are biased in favor of the sponsors’ products; findings that go against the interests of study sponsors never make it into print. | Ensure that your sponsors do not influence your study decisions—you should have access to all study data, should analyze the data and choose the study methodology independently, and should have the final say in preparation and submission of the manuscript.16 Always disclose funding sources and any conflict of interest. Manuscripts disclosing any funding source are more likely to be published than those without such a disclosure.11 |

Why you should proactively counter biases

Publication and reporting biases defeat the very purpose of research. By emphasizing the publication of positive results, these biases have built “a systematically unrepresentative” body of literature17 and have “led to scientific integrity being compromised.”18

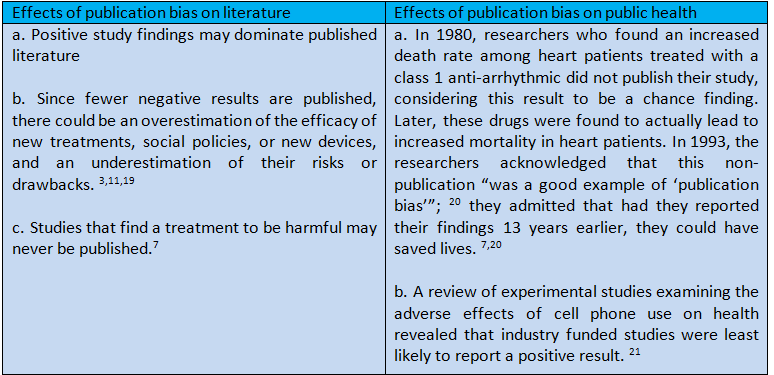

This can have adverse consequences, such as ineffective or dangerous treatments, prolonged suffering among patients, and wasted resources (See box: “Effects of publication bias”).

By countering publication and reporting biases, you can help maintain the integrity of scientific literature—by submitting methodologically sound studies that have not yielded the expected results; by highlighting the need to publish both negative and positive results; by conducting peer reviews objectively and without prejudice; by refusing to allow funding agencies influence study methodology, reporting of outcomes, or publication decisions.

A collective effort will ensure that published findings are more representative of all the completed studies and can help maintain the integrity of scientific literature.

Bibliography

- Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D. (Editors) (2008). Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (eds. JPT Higgins and S Green). Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration.

- Dickersin K (1990). The existence of publication bias and risk factors for its occurrence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 263: 1385–1389.

- McGauran N, et al. (2010). Reporting bias in medical research—a narrative review. Trials, 11: 37.

- Rosenthal R (1979). The "file drawer problem" and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3): 638–641. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638.

- Bodenheimer T (2000). Uneasy alliance—clinical investigators and the pharmaceutical industry. New England Journal of Medicine, 342: 1539–1544.

- Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP (2003). Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(4): 454–465.

- Song F, Parekh S, Hooper L, Loke YK, Ryder J, Sutton AJ, et al (2010). Dissemination and publication of research findings: An updated review of related biases. Health Technology Assessment, 14(8): iii,ix–xi.

- Mahoney MJ (1977). Publication prejudices: An experimental study of confirmatory bias in the peer review system. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1(2): 161–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01173636.

- Chopra SS (2003). Industry funding of clinical trials: Benefit or bias? Journal of the American Medical Association, 290(1): 113–114.

- Lesser LI, Ebbeling CB, Goozner M, Wypij D, Ludwig DS (2007). Relationship between funding source and conclusion among nutrition-related scientific articles. PLoS Medicine, 4(1): e5.

- Lee KP, Boyd EA, Holroyd-Leduc JM, Bacchetti P, Bero LA (2006). Predictors of publication: Characteristics of submitted manuscripts associated with acceptance at major biomedical journals. Medical Journal of Australia, 184: 621–626.

- Sridharan L & Greenland P (2009). Editorial policies and publication bias: The importance of negative studies (editorial commentary). Archives of Internal Medicine, 169: 1022–1023.

- Kotze JD, Johnson CA, O’Hara RB, Vepsäläinen K, Fowler MS (2004). Editorial. Journal of Negative Results—Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, 1: 1–5.

- Koricheva J (2003). Non-significant results in ecology: A burden or a blessing in disguise? Oikos, 102: 397–401.

- Leimu R & Koricheva J (2004). Cumulative meta-analysis: A new tool for detection of temporal trends and publication bias in ecology. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B271: 1961–1966.

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: Writing and editing for biomedical publication [Accessed: June 14, 2011] Available from: http://www.ICMJE.org.

- Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M. (Editors) (2005). Chapter 1: Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis in Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments (eds. HR Rothstein, AJ Sutton, and M Borenstein). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK.

- Editorial. The whole truth. New Scientist. May 1, 2004. Magazine issue 2445.

- Scholey JM & Harrison JE (2003). Publication bias: Raising awareness of a potential problem in dental research. British Dental Journal, 194: 235–237.

- Editorial: Dealing with biased reporting of the available evidence. The James Lind Library. [Accessed: June 14, 2011] Available from: www.jameslindlibrary.org.

- Huss A, Egger M, Hug K, Huwiler-Müntener K, Röösli M (2007). Source of funding and results of studies of health effects of mobile phone use: Systematic review of experimental studies. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115: 1–4.

Published on: Oct 29, 2013

Comments

You're looking to give wings to your academic career and publication journey. We like that!

Why don't we give you complete access! Create a free account and get unlimited access to all resources & a vibrant researcher community.